Wandering on Hoks – A World of Tracks Written on Snow.

One of my favorite things about Hoks is how they disappear when I take them out in the snow. Disappear? Let me explain. The Hoks are easy to ski on, so do not require a lot of attention during a good winter wander. Many types of skiing demand almost constant attention. Ski technique can require precision and focus to get your skis working right and behaving properly. A lot of the more recent gear innovations work well in a narrow set of circumstances but require quite a bit of adjustments and fiddling along the way. Modern backcountry gear completely separates the up from the down, discouraging any spontaneous digressions. Hoks let me click in and go, allowing me to let my attention and focus stray to things unrelated to my skis and skiing. I ski the Hoks exclusively with a tiak (single pole) as it is much easier for any down skiing and at worst a wash for general travel. The tiak also appeals to my perhaps over developed desire for minimalism, two poles being one more then you really need. With at least some of my attention freed up from skiing (along with one hand) I notice a lot more, and with my ability to be spontaneous – up down and around all being equally accessible – I find I am more observant. I also really enjoy taking pictures, something that aligns well with being able to let my attention wander. Last year and this year I started discovering and seeing more in various tracks, ski tracks, animal tracks, tracks left by wind and sun and shadows. There’s a lot out there. So here is a collection from this year and a few from last year. I will probably add and edit this over time. A lot are from skiing on Boulder Pass, which had a big and hot fire rip through in 2015, leaving large areas burned to various degrees. Sad to see these big old trees die, but in the winter the light and shadow as well as the contrast between white snow and blackened (now browning) trees is quite magical. Some of these are also from the Sherman Pass area and some are from around my home. They are all from my winter wanders on Hoks. SKI TRACKS

The Sami and Reindeer herding

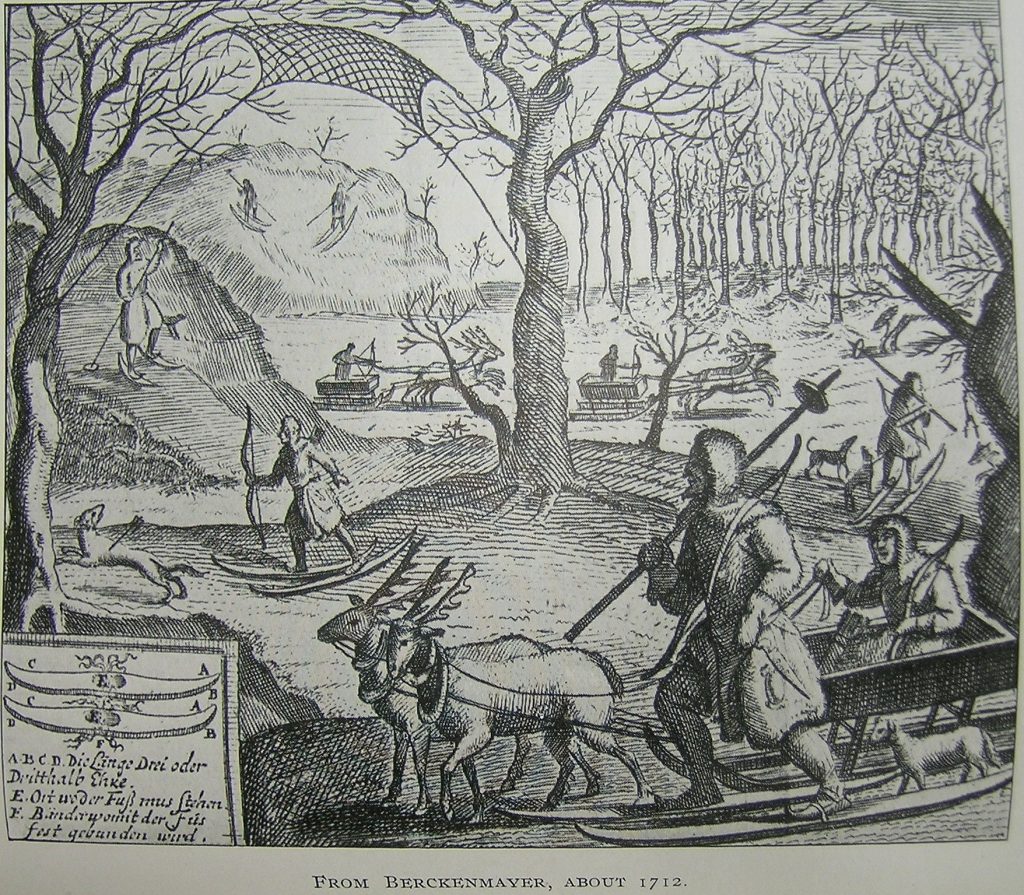

I found this video the other day on Atlantic ( a great website). Sami (they use to be called Laps) are believed by many ski historians to have introduced the more modern Scandinavians (Norwegians/Swedish) to skiing. There are some ski researchers that have put forth the idea that traditional reindeer herding was only made possible with the use of skis. Reindeer herding is believed to have started in the far east – north of modern day Mongolia – and spread north and west from there. All traditional reindeer herding cultures are documented to have used skis for herding, and some continue to use skis to this day.

Hoks in Mongolia

Skiing for Ethnoarchaeology in Mongolia In the summer of 2012, I initiated the Dukha Ethnoarchaeological Project. Ethnoarchaeology is the study of living people for the purpose of developing tools to aid in the interpretation of the archaeological record. I am an archaeologist at the University of Wyoming. I normally excavate sites of the first inhabitants of the New World, human occupations that are more than 10,000 years old. In those sites, we find hundreds or thousands of chipped stone artifacts and animal bones. Frustrated with my inability to make sense of spatial patterns in the archaeological record, I was inspired to study living people, people who still lived a traditional nomadic lifestyle, similar to those people I study archaeologically. I wanted to study how nomadic people use their living spaces and how the decisions that people make about how to use space relate to patterns in material residues left in the archaeological record. I turned to the Dukha, Mongolia’s reindeer herders who live in in the Sayan Mountains in Khövsgöl Province near the border of Russian Siberia. The Sayan Mountains are a cold place, which is why reindeer are able to live there. The taiga where I work, called the “Right” or “West” Taiga, is at 51° north latitude, equivalent to southern Canada. In the winter, nighttime temperatures regularly drop to -40° C and in the summer, daily highs top out near 20° C. The Dukha are ethnically Tuvan and have a tradition of skiing. In fact, Tuvan peoples may have been the world’s first inventers of skiing. That said, in my four field seasons in the taiga, I have only seen one pair of traditional skis. I saw those in a spring camp earlier this year. It seems as if traditional skiing is slowly fading from the Dukha cultural repertoire. My colleague, Matt O’Brien (California State University, Chico), and I purchased two pairs of Altai Hok skis for our fieldwork. We chose them for several reasons, but most importantly because they are short in length. They travel easily whether by plane, vehicle, horse, or reindeer. They are also wide, so they perform well in backcountry conditions. My graduate student assistant, Spencer Pelton, and I spent the night of April 15, 2016 in a winter camp in the Harmai Valley, southwest of the small town of Tsagaannuur. We had arrived to camp two days before and planned to move with a Dukha family into their spring camp high in the taiga. We had a day of rest on account of weather; it snowed for 24 hours following our arrival. The morning of the move, everyone packed their belongings onto deer, and we began the long two day ride into the mountains on the backs of reindeer. Sunlight glinted off of the snowy landscape as we rode into the mountains, and through our 500 m ascent, the snow grew deeper. In the valley bottom of winter camp, only 10 cm of snow had fallen. Where we camped that night in a place called Shamög, the snow was knee- to waist-deep. My Dukha friends made a roaring fire, and we drank tea, and ate bortsag (small pieces of fried dough) and boiled mutton ribs and back. An area was cleared of snow for sleeping. I had my -40° sleeping bag, but I was very happy when Khosbileg, my 18 year old Dukha little brother, put three layers beneath us (including a sheep skin blanket) and two more on top. I slept warm and comfortably under a million stars in a clear dark sky. We knew the next day would be difficult, but we did not know how difficult. Mankhen Pass stood between us and our destination at 2,825 m in elevation. We had to climb another 650 m from our campsite, and conditions were not going to get any easier. At first, our deer handled the snow well, but on a steep climb, I watched Khosjargal’s deer get bogged down in deep snow. Khosjargal is 20 years old and probably weighs 65 kg, too much even for his artic-adapted mount. After prodding his deer to regain its footing and failing, he turned to me and said in Mongolian, “My snow machine is out of gas.” He dismounted and started trudging up hill in waist-deep snow, pulling his deer behind. Our next two hours were like this. As we climbed upward, the deer struggled through deep powdery snow and Khosbileg and Khosjargal took turns breaking trail. The final climb to the pass was a challenge. It was very steep, and as we switchbacked up the slope, packs became unbalanced and fell off of exhausted deer. I pulled a train of three animals behind me as I walked up the last 50 m of ascent. There, struggling to regain my breath, I gave Spencer a high five, and said, “Let this officially be the end of winter.” I was so very wrong. The back side of the pass was worse than the front. The snow was still deep and powdery, and the trail descended slowly. We stayed in the alpine zone for more than 10 km. Exhaustion was setting in from a vicious cycle of dismounting from tired deer, pulling the deer out of the snow, remounting from a base of powdery snow, riding 5 m or 10 m if you were lucky, and bogging down again. After watching Khosjargal, his son, struggle downward this way for 45 minutes, Bayendalai rode up to me and said, “Can we use your skis?” “Of course!” I responded. Bayendalai is 59 years old. He was born and raised in the taiga. There is no one I would trust more in a difficult situation in the taiga than Bayendalai. I strapped on my Hok skis for the first time. Bayendalai tied two deer to my belt for me to pull behind, and I started skiing. I moved easily across the powdery snow, and the deer behind me, unburdened by my weight broke the trail for the

About This Site

Skishoeing.com is the companion site to our Altai Skis.com site. We thought it would be good to have a informational site dedicated to using skishoes in the many ways people do. You will find some posts on field work being done on Hoks, kids using them (the Hokstars!), schools, and some user posts as well. We also will add instructional information over time, using skishoes in different terrain and conditions, as well as the pros and cons on different bindings, and, of course, using the Tiaks (single poles). There will be lots of images (see the Gallery page) as well as some great new videos for this year. We welcome comments, user feedback, requests, and contributions. Happy Skishoeing! Nils Larsen

Skishoes in Minnesota

Hok skiing on the North Country National Scenic Trail I first heard of Hok skis several years ago from North Country Trail Association (NCTA) volunteers Jim & Jeri Rakness. They kept insisting that I really needed to try them out. At first, I couldn’t imagine what it was they were describing and, to be honest, I was a little skeptical. This is because I was quite happy snowshoeing, a favorite winter activity of mine. I’m lucky enough to snowshoe both for family fun and for my work for the NCTA. We usually scout and flag new sections of the North Country National Scenic Trail during the winter because we can actually see in the leafless woods and go more places when the ground is frozen. NCTA volunteer Bruce Johnson using Hok skis on the North Country Trail in Minnesota’s Chippewa National Forest (Photo by Matthew Davis) The last several winters here in northern Minnesota; however, have not delivered adequate snowfall for snowshoeing. So, last winter when I was invited to go out with some local NCTA volunteers on a backcountry ski outing I decided to finally try it. We went across a frozen lake and some connected wetlands/beaver ponds because there was only about 2” of snowcover on the ground. It was fantastic and love at first try with the Hok skis. This past fall, I purchased a pair of Hoks and anxiously waited for the first snowfall. I first tried them out at a January 2nd backcountry exploration hike in Itasca State Park (source of the Mississippi River’s headwaters). The conditions were perfect for the Hoks. Skiers and hikers explore the Itasca State Park backcountry (Photo courtesy of Kevin Cederstrom / Park Rapids Enterprise) Several other hikers asked to try out the Hok skis during the event. All enjoyed them and one person bought a pair that night. Spreading the word at NCTA’s Winter Trails Day events I also thought that backcountry XC skiing with the Hok skis would be a great addition to our Winter Trails Day events where we typically introduce people to snowshoeing. Last winter, I had only one attendee at a free Learn to Snowshoe Clinic because there just wasn’t enough snow for people to get excited about trying it. While this winter has delivered more snow than last year, it’s still not deep enough for me to need snowshoes – which are pure work to walk with when they’re not needed for flotation. I was hoping that the inclusion of the backcountry XC skiing component and having pairs of Hoks on hand for people to try out would attract more interest. That turned out to be the case. On January 30th, we hosted a Winter Trails Day event at the MSUM Regional Science Center just east of Fargo, ND. While the crowd was small (there was a big winter festival going on in town), everyone there was excited to try out the Hok skis. We found a little patch of wind drifted snow in the prairie and people skied around and enjoyed themselves. Several participants commented that they were going to look at buying a pair. We hosted a Winter Trails Day event on February 6th at Detroit Mountain Recreation Area in Detroit Lakes, MN that drew a good crowd. While most admitted they were there to try snowshoeing, several did venture out on the Hok skis and had an enjoyable experience. A few inquired about where they could buy a pair. Later that afternoon, we had a new participant show up for our guided hike/ski on the North Country Trail and she really enjoyed it. After these experiences I’m convinced that if people interested in winter sports will try a pair of Hok skis they’ll love it. Many will want to purchase a pair. I can envision a time – maybe five or ten years from now –when local outdoors stores in northern Minnesota will carry Hok skis. At this same time, our guided winter events on the NCT will feature equal numbers of snowshoers and Hok skiers. A new skier trying out the Hok skis at the Winter Trails Day clinic at Detroit Mountain Recreation Area (Photo by Matthew Davis) Jim & Jeri Rakness and I enjoy the NCT on a Wildlife Tracking Trek (Photo by Matthew Davis) Top 5 reasons why Altai Hok skis are perfect for the North Country Trail: Because lately we haven’t received good enough snow for snowshoeing or XC skiing. While these are the more traditional winter silent sports activities here in MN & ND, they do require more snow than Hoks. Because they are more efficient in covering ground than snowshoes and winter hiking. You have the ability to glide on each step and also to ski down the hills. Because you can go just about anywhere with them on – across a frozen lake, up a frozen river, down a trail, etc. Because they are so well made and durable. Because they’re tons of fun!

Moose Population Study – Yellowstone National Park

My wife Lisa and I initiated a 3 year non-invasive moose population study in the Northern Range of Yellowstone National Park and adjacent Custer-Gallatin National Forest in 2013. The goal of the study was to use non-invasively collected DNA to estimate population size and parameters of the northern Yellowstone moose.

Tracking cougars in Yellowstone

The National Park Service’s Yellowstone Cougar Project embraced the Hok skis for their winter field work studying Yellowstone’s most elusive large carnivore. Biologists have been conducting intensive snow-tracking surveys in Yellowstone’s rugged winter terrain to detect cougar tracks and follow them through common travel routes to bed sites, scent marking sites, and prey remains.